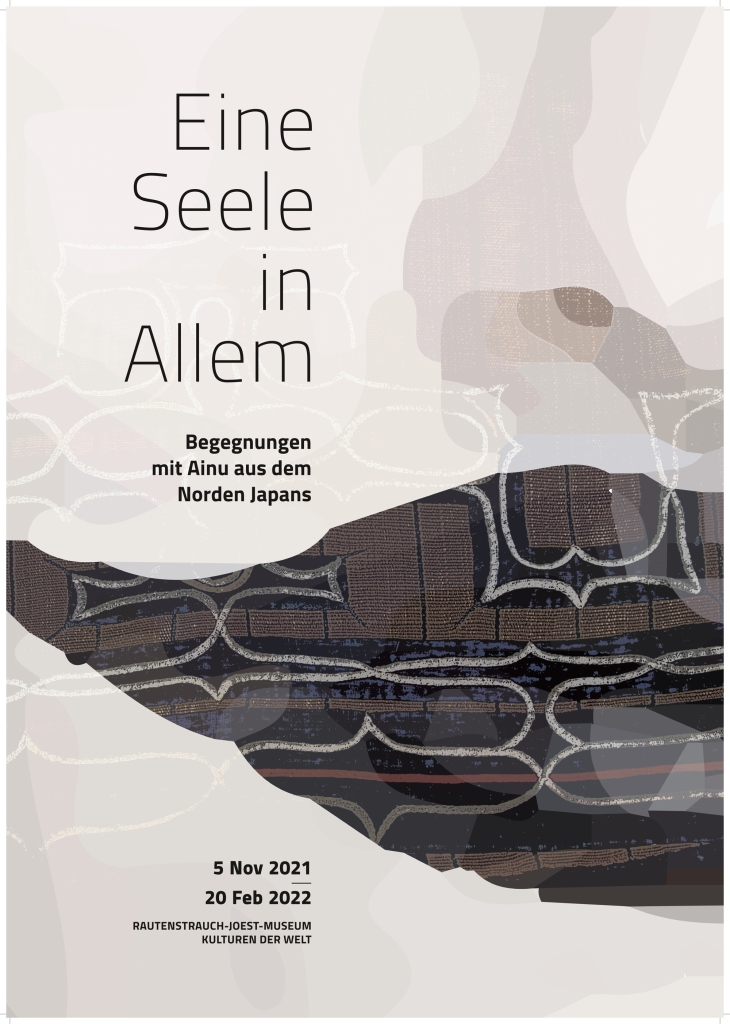

The Ainu are considered to be the indigenous people of Northern Japan who originally lived as hunter-gatherer communities mainly on the islands of Hokkaido and Sakhalin. On 5 November 2021 a new exhibition about these people opened at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum (RJM) in Köln. The exhibition, which is called A Soul in Everything – Encounters with Ainu from the North of Japan, closes on 20 February 2022.

I am honoured to present below an article about the exhibition written by the curators OATG member Walter Bruno Brix and Dr Annabelle Springer (RJM).

For Ainu, everything is animate – from mountains and waterfalls to small everyday items. This spirituality has always been of elemental importance to Ainu groups in Northern Japan and remains a central element of their cultural identity today. In their imagination, there is a living/inhabiting “soul” (kamuy) in almost everything that communicates with people. In the Köln exhibition, the beauty of things is made visible. It gives an insight into the history and resistance movement of Ainu groups and at the same time an impression of the beauty of their material and immaterial culture, complemented by contemporary artistic positions.

The cooperation with the National Ainu Museum, Hokkaido, Japan and the scientists affiliated there enabled deeper insights into Ainu cultures. In close exchange with representatives of Ainu groups, aspects of handling the things were discussed from a curatorial, restorative, and conservation-ethical perspective. Contemporary artistic positions were intensively integrated into the processual creation of the exhibition and elaborated for the exhibition.

These include video works by artist and Ainu activist Mayunkiki, in which she reflects on what it means to be ‘Ainu’ and thus being part of a social minority in Japan; poignant portraits of both old and young generations of Ainu by Italian documentary photographer and director Laura Liverani, who thus sets a counterpoint to the historical portraits of Ainu in the RJM’s photographic collection; video projections by French artist Boris Labbé that intertwine duplication, reflections, and interweaving of the patterns of Ainu textiles and onomatopoeia of Ainu chants; and the dance works of Norway-based Ainu activist and artist Dr. Kanako Uzawa, who not only stimulates a sensitisation in the perception of minorities, but also responds to Ainu traditions in her artistic works.

The Collections in the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum

The museum’s collections include 203 items that can be attributed to Ainu groups, as well as 80 historical photographs by Polish photographer Bronisław Piłsudski, who traveled to Ainu areas in the late nineteenth century. At that time, Western interest in Ainu cultures was high. They were idealised as good-natured and noble, in line with a romantic version of Rousseau’s notion of the “noble savage.” In Germany, moreover, the thesis of Ainu as a “missing link” between “Asian” and “European” people was intensively pursued. As a result, interest in their culture grew steadily. This was also the case with Wilhelm Joest, who traveled to Hokkaido in 1881 and from whose collection 18 items have been preserved by the museum. At the same time, antique and ethnographic dealers such as the Johann Friedrich Umlauff company sensed opportunities for lucrative business. In 1906 and 1907, more than 700 things from Hokkaido and Sakhalin were first offered to the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum by the Hamburg company Umlauff. The Foundation for the Promotion of the Museum acquired 220 numbers for the collection. In the further course of the twentieth century, interest in the cultures of the Ainu ebbed away, as evidenced by the small number of only three additions from private collections within the following 106 years.

The Köln collection includes ethnographic things such as tools, knives and other weapons for hunting, as well as arrows and bows, lances and fishing accessories. Also plates, bowls, spoons and mashers for preparing and serving food. Ceremonial items include libation spatulas (ikupasuy), prayer sticks (inao), and amulets. An important inventory is the numerous textiles that were elaborately handcrafted by Ainu women. These include bags made of elm bast, carrying straps, robes, belts, headdresses, gloves and footwear, a small but important selection of which is presented in the exhibition.

A New Way of Dealing with Things

Things were reclassified not only from a curatorial perspective but also from a restoration and conservation perspective. The visit of a Japanese delegation in 2019 to study Ainu-related collections in European museums allowed things to be reclassified. Most of the things in the collection are made of perishable natural materials such as wood, bark, and fibres and undergo a process of change over time: they age, become brittle, or change in colours and textures. Slowing down these processes and thus documenting and preserving the things and all the information they contain for the future is the task of conservators. In the exhibition “A Soul in Everything” Petra Czerwinske, Kristina Hopp and Stephanie Lüerßen were responsible for this. They were also in close contact with colleagues from the National Ainu Museum and representatives of the Ainu from the very beginning. In addition to material-technological aspects, they discussed the handling of the things from a restorative and conservation-ethical perspective. In addition, in cooperation with the Institute for Restoration and Conservation Sciences at the Technical University in Köln, three textile items from the collection were examined and their materials and manufacturing techniques determined. In this way, valuable findings were obtained, which are presented in the exhibition.

Elm bast and embroidered silk

In the case of Ainu textiles, two main sources come together: on the one hand, Ainu women made garments from a variety of materials. These included fish skins, bird skins, and furs from hunted animals, but fabrics were also made from the bast fibres of trees such as linden and elm and from the fibres of nettle, and mats were woven from rushes. In contrast, textiles imported from Japan, China and Russia were made of cotton, wool or silk. In most cases, these were so precious that they were only used to decorate the homemade materials.

© Rheinisches Bildarchiv (RBA), photographer: Anja Wegner, rba d055073_02

The textile highlight in the exhibition is a complete nineteenth century garment made of elm bast (attush amip), decorated with appliquéd patterns. The plain weave fabric was made on a simple loom in which the weaver controls the tension of the warp threads by means of her body posture. Fine stripes of dark blue cotton threads are woven in at irregular intervals between the warp threads of bast fibres. Two of the fabric strips with a width of about 40 cm were laid over the shoulder and sewn together to form the body, while two other shorter ones were ingeniously folded in a triangular shape and attached as sleeves. Along the hems and the collar, wide ribbons run around the robe. A complex symmetrical pattern is appliquéd on the back and in the lower part. This consists of wide stripes of indigo dyed cotton fabric from Japan, and narrow curved interwoven lines above. These are also made of imported tabby weave cotton fabrics. The fact that these line patterns were not embroidered with threads, but rather appliquéd from narrow strips of fabric, indicates that this garment originated from an Ainu group from Sakhalin that no longer exists today and was forcibly resettled to Hokkaido in 1875 [note 1].

© Rheinisches Bildarchiv (RBA), photographer: Anja Wegner, rba d055073_02

The bands around the openings and the applied patterns are meant apotropaically, that is, to protect the person wearing the robe. The Ainu expression for this is sermaka omare [note 2]. Characteristic of Ainu patterns are spiral or bracket-like shapes (kiraw) and thorns (ayus) attached to the corners.

Three smaller textiles are presented lying in a showcase and give an insight into the work of the three students (Viola Costanza, Tjarda Rauh, Anastazia Zitzer) of the TH Köln. One of them is a small bag (ketush; Inv. No. 253251) that was also sewn together from elm bast with woven-in warp stripes of indigo cotton. In this case, the stripes are more complex and groups of two equal stripes alternate with three stripes of different widths. Several pieces, possibly remnants of a garment, were put together and bordered with a surrounding band of dark dyed cotton.

The bag was worn with a cord loop on the belt. However, this is now torn and pulled out of the original openings in the flap. Whether this happened in use or was done intentionally to release the inherent ‘soul’ (kamuy) before giving it away cannot be determined with certainty today.

A small piece of silk wadding (Jap. mawata) is found under the folded-over flap. Possibly this sticky silk wadding once had a counterpart, so that it functioned like a kind of Velcro, or the wadding was used in making fire. Indeed, in this bag were kept bullets and a lighter for hunting.

Also presented here is a tiny sleeveless jacket (Inv. No. 254391) for an infant. This one is made of tabby weave cotton, dyed dark brown or discoloured, partially with a printed fabric. The chrysanthemum pattern of this lining on a turquoise blue background points to an origin in China. All in all, the entire vest was probably imported from China [note 3]. A clue to this is also provided by the designation of this jacket in the purchase documents of 1907, where it is described with the Ainu word ‘imi,’ which Batchelor translates as: “Generally Japanese clothing. Clothes made after Japanese fashion. Sometimes any clothes” [note 4].

The third textile shown here (Inv. No. 254451) consists of four sections of a Japanese robe and two other Japanese fabrics. The four sections of damask silk on the upper side have been elaborately dyed and come from a sumptuous ladies’ robe (Jap. kosode) of the nineteenth century. The woven damask patterns show scattered flowers on a background of linked swastika. This type of damask silk was originally imported from China, but was also made in Japan during the nineteenth century. On the creamy white silk, the motifs of blooming chrysanthemums, maple and pine trees among clouds and stripes of mist were reserved with a rice paste. This was applied by hand before the fabric was dyed dark brown. After removing the rice paste, the patterns stand out light on a dark background. Details such as leaf veins were added in fine ink painting. Coloured silk and gold threads were used to additionally over-embroider some of the patterns. The reverse side consists of two Japanese fabrics, which were also patterned with rice paste in a reservage technique. Stencils were used on both. The blue fabric is decorated with flowers in rows, the brownish one shows fine dots (Jap. Edo komon), which are ordered to a dense flower pattern. What the narrow elongated cloth was used for in the Ainu culture has not yet been clarified. Certainly it was a treasured thing that was highly valued.

Another highlight of the collection is a small triangular amulet (Inv. No. 253071) made of glass beads. This was woven into the forehead hair of the boys and when this part was shaved after his first successful hunt, the amulet also fell away. The small glass beads are threaded together and then sewn on a base of a Japanese fabric. This is woven in fine plain weave, whether of cotton or linen could not be investigated so far. There is a fine dot pattern on an indigo blue ground, which was created by applying rice paste using a stencil before dyeing.

The exhibition presents important historical Ainu textiles. In addition, the traditions behind these textiles are also made accessible in other ways. Thus, it is possible to touch two different pieces of the rare attush fabrics. One of them is more modern and without signs of use. Here the surface is still rough. The other piece is older and is softer on the surface because of frequent use and being washed several times. The density and thickness of the weaving threads of both pieces is also different.

Other features include two videos showing the textile craft techniques that have been handed down to the present day. One of the videos shows the weaver Yukiko Kaizawa making a length of fabric from elm bast fibres (attush). As she shows the steps of making it from fibre extraction to dyeing to the finished woven piece, she talks about her life. A second video shows Ikuko Okada sewing an Ainu garment (ruunpe) from the Shiraoi area and decorating it with appliqué. She also talks about her view of her work and the traditions she preserves.

The exhibition “A Soul in Everything – Encounters with Ainu from the North of Japan” gives a deep insight into the history of the museum collection, the traditions of Ainu groups and their beliefs. At the same time, it makes voices of Ainu of today and their way to recognition audible in a variety of ways.

Notes

- Josef Kreiner, Hans-Dieter Ölschleger: Ainu – Jäger, Fischer und Sammler im Norden Japans Bestandskatalog RJM Köln, 1987, S. 86, Kat. No. 133. Mashiyat Zaman: The Ainu and Japan‘s Colonial Legacy, posted 23.3.2020, retrieved 8.11.2021.

- Kristie Hunger: Sermaka Omare: The Ainu Motif of Protection. An Analysis of Traditional Ainu Artwork. 2017.

- Oral hint thanks to Yoshiko Wada.

- John Batchelor: An Ainu-English-Japanese Dictionary, 2nd ed., Tokyo 1905, p. 173.

OATG members may recall that we had planned a trip to the RJM for the summer of 2020, but alas were forced to cancel it. Hopefully this can be rearranged for the future as the museum really is worth spending time in. To get some idea of the scale of this museum and its textiles please take a look at this blog I wrote in 2019.